Why Liberals Should be Conservative: Climate Change, Excellence, and the Practice of Happiness, Part 2

Ed. note: Part 1 of this series can be found on Resilience.org here.

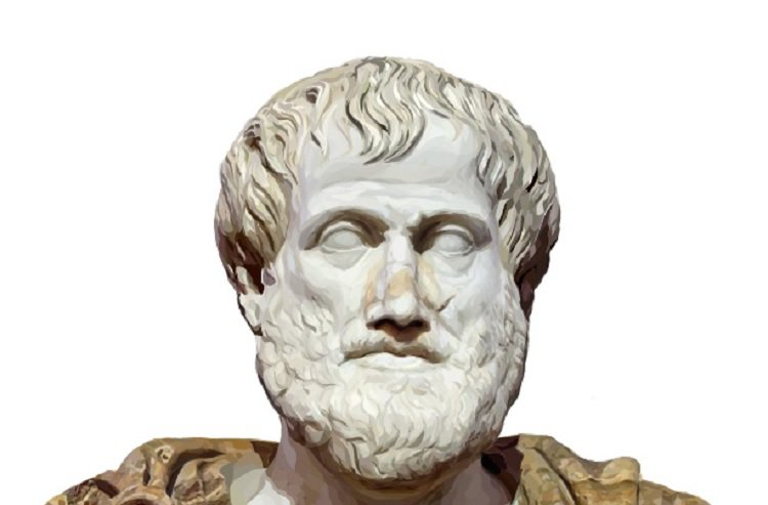

The Resurgent Aristotelians: Hopkins, Fleming, Francis, and Holmgren

What then does a modern Aristotelianism look like? How might we reconcile his ideal of a singular, philosophically deduced definition of a “good life” with modern pluralism and heterogeneity, and the Liberal insistence on individual expressive self-creation? How do we define “good” or “excellence” without imposing an ideology or world-view on others who have their own? Who judges and according to what standards? If such a reconciliation is impossible, will we be required to make a difficult choice? Or is there no real choice at all?

These are the questions that I will be considering, and to which in some cases I will hazard an answer, as we go forward. To start that process, a quick recap may be in order. I have outlined a philosophical and political standoff between Liberalism and a still-being-defined conservative Aristotelianism using common terminology, but in a particular way that may also need clarification. I take Liberalism to represent the broad post-Enlightenment political and moral philosophy that has found its home in societies organized around a market economy, in which the primary location of agency, obligation, and desert or rights resides in the individual, who is freed from the “constraints” of “kinship, neighborhood, profession, and creed,” and given over to seemingly voluntary “freedom of contract” (Polanyi, 171). Liberalism, as I use the capitalized version of the term, includes both political liberals or progressives of the sort that one might associate with Democrats, the Labor party, or Democratic Socialism, on the one hand, and “conservatives” (with scare-quotes) of the sort associated with Republicans, the British Conservative Party, and Christian Democrats, on the other.

…click on the above link to read the rest of the article…