Today’s Contemplation CLXXIII

Human Ecological Overshoot: What to Do?

Today’s Contemplation is a very short comment I posted on The Honest Sorcerer’s latest piece.

News and views on the coming collapse

Home » Posts tagged 'today’s contemplation' (Page 6)

Human Ecological Overshoot: What to Do?

Today’s Contemplation is a very short comment I posted on The Honest Sorcerer’s latest piece.

Yes, the grieving process must be travelled through to the end to reach ‘acceptance’ of our human ecological overshoot predicament. Some are just beginning this process and as such display the very typical denial and bargaining stages, thinking quite adamantly that human ingenuity and our technological prowess will triumph over any and everything that Nature has in store for us story-telling apes. In fact, it’s not unlikely that the vast, vast majority of people are not even remotely aware of the human ecological dilemma and attribute growing signs of ‘collapse’ to socioeconomic and sociopolitical factors solely.

For myself, it took a number of years to move through these grief stages and I still get bogged down in some ‘hopefulness’ periodically that we can avoid what is for all intents and purposes inevitable (I think mostly because I have children whom I’d like to think can ‘dodge’ the ramifications of the coming storm).

Aside from this psychological journey of grieving, I wrote a series of Contemplations (starting here) about a number of other cognitive aspects that impact our belief systems and thinking about this, concluding that:

“The collapse that always accompanies overshoot seems baked in at this point with little if anything we can do about it.

Personally, I’d like to see our dwindling fossil fuels dedicated to decommissioning safely those significantly dangerous complexities we’ve created (e.g., nuclear power plants, biosafety labs, chemical storage, etc.) and relocalising as much potable water procurement, food production, and regional shelter needs as possible rather than attempting to sustain what is ultimately unsustainable given the fossil fuel inputs necessary. Perhaps, just perhaps. by doing these things a few pockets of humanity (and many other species) can come out the other side of the bottleneck we’ve created for ourselves.”

Your call for focusing on a ‘graceful landing’ immediately had me think about Dr. Kate Booth and Tristan Sykes ‘Just Collapse’ initiative. They describe it as “an activist platform dedicated to socio-ecological justice in face of inevitable and irreversible global collapse…[that] advocates for a Just Collapse and Planned Collapse to avert the worst outcomes that will follow an otherwise unplanned, reactive collapse…[and] advocates for localised insurgent planning and mutual aid.” And this avenue may be the best path to follow at this point, particularly since it appears that most of our reactionary attempts to stave off the symptom predicaments of our overshoot are serving to exacerbate our issues.

Human Ecological Overshoot and the Noble Savage

Wanted to share yet another online discussion that arose in response to a comment link (see below) posted on my Contemplation regarding electric vehicles (see: Blog Medium) within one of the Facebook Groups I posted it to (Prepping for NTHE).

I share this as a means to spur thinking about the rather linear and simplistic cause-effect attributions that humans tend to make and that Dr. Bill Rees discusses near the beginning of the interview that forms the start of this thread–he attributes it to our nervous systems/brains evolving in relatively unchallenging environments where our thinking could be straightforward (e.g., Is this plant edible? Will this animal eat me? Should I seek shelter?). Homo sapiens’ brains did not evolve in an environment where one may need to consider complex systems with non-linear feedback loops and emergent phenomena, nor where social interactions with many dozens, perhaps hundreds of people, over short periods of time took place.

We now find ourselves in a very different world with very different circumstances and far, far more challenging environments. While we have become increasingly aware about our place in a very complex universe, we have only recently stumbled across an exceedingly complex predicament that we appear entangled within. I am, of course, speaking about human ecological overshoot with equally complex symptom predicaments (e.g., biodiversity loss, climate change) of this overshoot.

As a result of our brain’s evolutionary past, our thinking about these predicaments tends to become focused upon singular causal agents that we like to believe we can understand and then address, usually via of our ingenuity and technological prowess. This approach tends to lead us away from the significant complexities that exist.

Evidence is mounting that there are a number of causal agents to our overshoot and they are interacting in complex, nonlinear ways. Our attempts to untangle these so that we may ‘right the ship’ are, for all intents and purposes, impossible. In fact, our efforts to do this are for the most part exacerbating our predicament for a variety of reasons, and making the situation even more complex.

Perhaps the most significant impediment to our ability to mitigate overshoot — beyond the sheer complexity of it all — is our notion of human exceptionalism that Dr. Rees raises. By believing that humans stand outside or apart from Nature we miss/ignore/deny the dependence we have upon and interconnectedness we have with our natural world and its various ecological systems. We tend to hold that we can control and thus predict Nature so we can ‘solve’ overshoot.

Reminds me of the saying (sometimes attributed to Sigmund Freud) that ‘Man created God in his own image’…

Anyways, the innate tendency to expand that Dr. Rees highlights and forms the basis of the following discussion does seem to be a foundational cause–along with our tool-creation/-using acumen that provides our species a distinct advantage over others, helping us to extract and exploit resources to expand upon the natural carrying capacity of our environments and avoid the predation from most other life.

Thanks to JS for the conversation and forcing me to reflect on the issues and clarify my own thinking…

JL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GddxjCGlfiM

JS: JL, Major shortcoming. Rees attributes the growth imperative to “human nature.” In fact, all pre-capitalist societies did not have such an imperative, and grew only in an opportunistic manner here and there, with the norm being extended periods of steady state. Capitalism cannot do even slow growth, let alone steady state. He is clearly tied in his thinking to capitalism.

JL: Since it is apparently most of the current paradigm, I concur.

Me: JS, Not sure I agree. While I believe our current economic system — especially its ability to pull growth from the future via credit/debt creation — has turbo-charged our growth (as has our leveraging of hydrocarbons, and probably significantly more than economics has), most sources tend to trace ‘capitalism’ back to the 17th/18th century, some others to the Middle Ages (ca 14th century). But one hell of a lot of complex societies/empires/civilisations existed and tended to grow (too much) and then ‘simplify/collapse’ prior to this time, supporting Bill’s growth imperative argument — to say little about our species’ expansion from its beginnings on the African continent…growth does seem to be in our nature, especially once we had food surpluses.

DW: JS, capitalism can be thought of as a living entity, after all it is an extension of our minds which are driven by a biological need to breed. Nature has natural negative feedback, humans do not anymore thanks to fossil fuels, at least for now.

JS: Steve Bull: The Roman Empire was pretty much static for several centuries. The Mayan and Incan Empires did not expand beyond the ability of the imperial forces to control. Again static for centuries. There was no economic growth imperative during Feudal Europe. No pressure to grow or die till the advent of capitalism in late Medieval England.

Ellen Meiksins Wood Agrarian Origins of Capitalism

https://monthlyreview.org/…/the-agrarian-origins-of…/…

MONTHLYREVIEW.ORG

Monthly Review | The Agrarian Origins of Capitalism

JS: DW: See my response to Steve Bull right above. ^^^

Me: JS, I believe there would be many pre/historians who would disagree with your assertion that the three empires you name were ‘static’ for centuries; or any for that matter. And if they were, it was not because they didn’t want to pursue growth; it was because they no longer could ‘afford’ to.

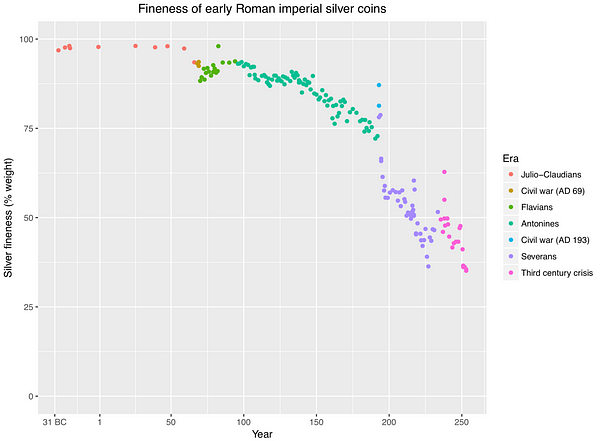

In fact, archaeologist Joseph Tainter looks at two of these in detail (Roman, Mayan) and appears to conclude that both of these expanded until they no longer could due to diminishing returns on their investments in complex expansion. Once they reached their expansionary ‘peak’, they began to use surpluses or other means (e.g., increased taxes and currency devaluation; increasing warfare; expansive agricultural/hydraulic engineering) in an attempt to maintain the status quo that on the surface would have appeared as being ‘static’.

In both cases the expansionist policies reach a peak and some semblance of continuity was achieved by depleting their capital resources to sustain themselves for as long as possible, but their people were experiencing tremendous and increasing stress over those years — until the costs of supporting their sociopolitical system were well above any perceived benefits and they ‘walked away’ leading to societal ‘collapse’.

It seems that as with any biological species, humans will ‘grow/expand’ in population (and thus planetary impact) if the resources are present. If the resources or the technology to help procure such resources (be it accessing hydrocarbons, hydraulic engineering to increase food yields, military incursions, and/or financial/monetary accounting gimmickry) are not present, then that growth will not tend to occur much past the natural environmental carrying capacity — as seems to be the case for many smaller, less complex societies.

Yes, human expansion/growth is limited but probably not because we don’t have a desire to pursue it but because there are hard, biogeophysical limits that we cannot overcome; when we can overcome them as has been the case for some large, complex societies (mostly due to their ‘technologies’ that have helped them to increase available resources), it seems we tend to grow/expand.

Throw on top of this tendency of a species to grow/expand when the resources are available a one-time cache of tremendously dense and transportable hydrocarbon energy that allows the creation of all sorts of tools to expand our resource base almost unimaginably and a monetary/financial/economic system that can appear limitless due to credit-/debt-expansion and hypergrowth seems inevitable and virtually impossible to control/halt…no matter how many of us understand the double-edged nature of this expansion on a finite planet.

JS: Steve Bull: Those empires had the OPTION to not grow given it would be too expensive. Under capitalism, there is no such option. Only twice before has global capitalism entered a period of no growth/negative growth lasting more than a year or two, and i’m talking on GLOBAL terms. This was in the early 1910s, and in the 1930s (starting in late ‘29). Both these situations led to world wars. The global system has been doing its best to avoid a collapse for 5 decades now. A collapse was prevented in late 2019 only via the largest ever injection of money by the world’s central banks, and this led to the shutdown of 2020, basically putting the world’s economy into an induced coma. Excellent analysis of this by John Titus at “The Best Evidence.” This is his most recent video, from October.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W0u5h579ZeU

YOUTUBE.COM

Presenting the Fed’s Perfect Plan for U.S. Dollar Oblivion

JS: Steve Bull: and from the other side of the political spectrum, but with the same conclusions, “Marxist” Fabio Vighi.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IjCwEv4luB8

YOUTUBE.COM

Endless emergency? The Lockdown Model for a System on Life Support | Prof Fabio Vighi

Me: JS, While I don’t disagree with the additional and significant pressure placed upon current human systems to continue growing due to the economic/monetary/ financial systems that they employ (a debt-/credit-based currency being a significant factor), I believe that the biological/physiological imperatives may ultimately be more influential in the long run and, as Bill Rees argues ‘natural’. It is not just human populations that expand to fill their environments based upon available resources but all species. Throw on top of this consideration the Maximum Power Principle that Erik Michaels has emphasised in a number of his articles and it would seem we are at the mercy of our genetic predispositions.

The ability of us naked, story-telling apes to employ a variety of tools (from agriculture to modes of economic production, and everything in between — but especially leveraging energy from hydrocarbons) to influence our resource extraction and use — has turbo-charged our natural growth/expansion tendency. It seems only when we have reached hard, physical limits to that do we stop. In fact, it appears we almost always go over our natural carrying capacity in one way or another (overshooting it) because of our tool use and attempt to extend our run, but then we are forced to contract/simplify…but not by our choice; it is usually by way of external factors, be they economic or ecological.

Despite the ‘option’ of not overshooting natural limits being theoretically possible (and, certainly, the best one to pursue), it seems our species rarely if ever do so willingly. Intelligent, just not very wise.

JS: Steve Bull: With capitalism, there is not gonna be any respect to natural limits, no matter what. Slow growth is not gonna be an option. Pedal to the metal, till extinction. Previous societies did eventually pay attention to these limits. This pressure by capital is not “significant,” it is overwhelming, impossible to overcome within capitalism. “Money doesn’t talk, it swears.”

Me: JS, I’m not convinced many if any societies willingly respected natural limits. Slow or no growth was imposed upon them. Humans like to believe we have agency in such matters but I am increasingly unconvinced of that.

JS: Steve Bull: you’d have to explain thousands of years of stable indigenous societies in the Western hemisphere before colonial times.

And there is no imposing any limits on capital. It will destroy the planet an all humans if that’s what it takes.

JL: In the final analysis, overshoot prescribes that we ultimately fail, much like the previous civilizations in past history. We continue to expel other life as we make our way to our perceived rewards which will be that we cause our own penultimate extinction or reduction to meaningless numbers. Humans cannot be the only life around, although they live like they are the only organism above most life extant…

Me: JS, An FYI that I am penning a somewhat lengthy response to your last comment that I am going to post as a new Contemplation, hopefully in the next few days — a tad distracted with ‘holiday’ commitments.

Here is my Contemplation response:

Me: JS, It’s been a few decades since my graduate work in Native anthropology/archaeology but I believe the idea that you are expressing — that prior to European contact and colonisation, indigenous societies in the Western hemisphere were ‘stable’ for thousands of years (and if we rid ourselves of capitalism we can return to this state) — is a derivative of the Noble Savage narrative that arose in 16th-century Europe not long after increased interactions with Native societies in several locations about the globe[1], and influenced a lot of subsequent thinking.

This view that ‘primitive’ peoples who lived outside of ‘civilisation’ were uncorrupted, possessed an inner morality, and lived in harmony with Nature filtered throughout Western intellectual circles, particularly within political philosophy where attempts to justify a centralised government raged.

Thomas Hobbes in particular applied this notion to American Indians. Jean-Jacques Rousseau furthered it by arguing the natural state of humans was of innate goodness but that urban civilisation brought out negative qualities. Literature also played a role in propagating this view of Native societies with such works as Henry Longfellow’s poem The Song of Hiawatha and James Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans. In essence, civilisation=bad/corrupted and native=good/uncorrupted. Thus arose the justification/rationalisation/’need’ for central government oversight in large, complex societies.

Not surprisingly, given their widespread acceptance within academic/philosophical circles, early anthropologists/archaeologists adopted these ideas as their studies on the ‘other’ expanded. As anthropology developed, however, these views have been criticised as being overly romantic, serving political purposes, and, perhaps most importantly, on the basis that they contradict ethnographic and archaeological evidence.

Turning back to our discussion about societal stability and ultimately whether human societies grow beyond limits due to a capitalistic economic system or as an innate tendency, the vast array of complex indigenous societies that covered the ‘New World’ engaged in a variety of behaviours that can be considered quite ‘unstable’ and certainly in contrast to the stereotype of a ‘Noble Savage’.

Early on during the human occupation of the Americas there were many nomadic, hunting and gathering tribes that had little impact upon the ecological systems that they depended upon and could easily migrate to unexploited regions when the need arose but mostly because their resource needs required it. But even during these relatively ‘stable’ times (that seems to have been due primarily to resource abundance and low population pressures) humans were having a significant impact upon the native species, hunting several large mammalian species to extinction[2].

Then, as elsewhere in the world, once food surpluses were established (primarily due to the adoption of agriculture, which has been argued was a response to population pressures[3] after which positive feedback loops kicked in leading to an explosion in population numbers) a variety of large, complex societies developed. And pre/historical evidence has demonstrated that these societies are not ‘stable’. They grow, reach a peak of expansion/complexity, and then simplify/collapse.

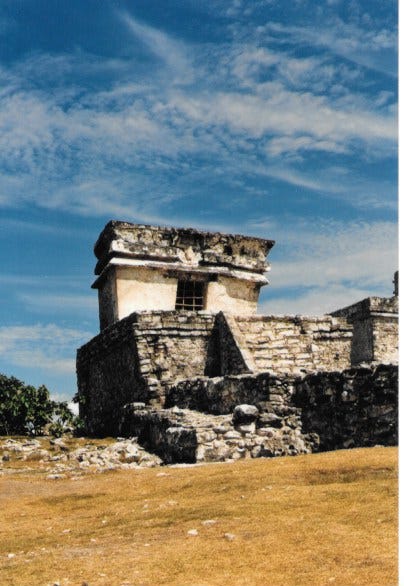

In the ‘New World’ these societies followed a similar path to those of the ‘Old’: competed (often viciously) over resources with neighbouring competitors; were not only quite hierarchical in nature with significant inequality but some included slavery and even engaged in human sacrifice; and, on occasion, degraded their environments to the point of ‘collapse’ with many forced to migrate.

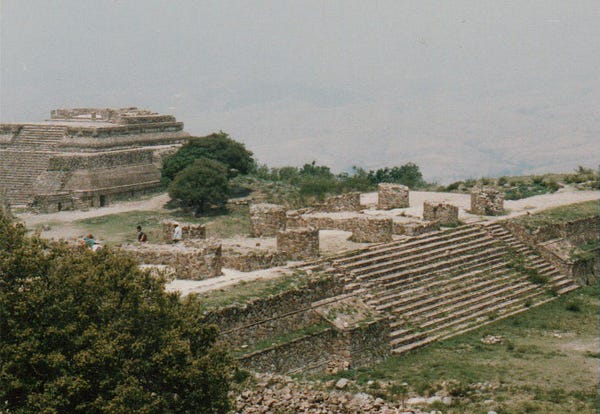

There were the well-known societies of the Maya, Inca, and Aztec. There were also the lesser-known societies of the Toltec, Mississippian, Mixtec, Moche, Teotihuacan, Iroquoian, Chimu, Olmec, Zapotec, and Chakoan, just to name a few[4].

None of these complex indigenous societies engaged in modes of production that would be considered capitalism but they certainly engaged in behaviours that would be considered detrimental to long-term sustainability and some experienced overshoot of their local environments. Archaeological evidence points to every one of these societies growing in complexity and expanding until a ‘peak’ is reached after which a societal transformation/shift occurred in which sociopolitical complexity was lost and living standards ‘simplified’.

The narrative that there was thousands of years of stability amongst indigenous societies prior to European colonisation does not reflect the evidence. It has been argued that environmentalists have adopted the belief that indigenous societies were ‘stable’ before Europeans for purposes similar to that of the political philosophers in the 16th-18th century: the belief is being leveraged for narrative purposes[5].

This does not mean that indigenous societies and some of their perceived sustainable practices should not be studied nor disseminated in attempts to correct some of our errant ways and perhaps help to mitigate marginally our overshoot. This could be said to be appropriate for every society, provided we could agree on what is truly ‘sustainable’ — there’s ample evidence that much (most? all?) of what is being marketed as such is anything but.

Dr. Rees’s contention that humanity expands from an innate predisposition is more about humans being part and parcel of Nature, and that we are a species like all others in that we are driven by genetics to propagate and expand. We do this and are successful (or not) based upon a number of ecological factors not least of which are the resources available and the factors that attempt to keep our numbers in check. As an apex predator with tool-making abilities, our expansion has been basically unchecked and thus the human ecological overshoot predicament we have found ourselves in.

While many do argue that human societies have tended to grow and broach regional and/or planetary limits due to their modes of production, it’s not as simple or straightforward as it being exclusively or even mostly due to ‘capitalism’ or some similar phenomenon. Yes, our current economic systems are horrible for ‘sustainability’ and attempts to reduce our extractive/exploitive processes. If we cannot, however, overcome the innate tendency to propagate and expand, and leverage our tool-making abilities to push beyond the natural, environmental carrying capacity, then even radical shifts in how we organise our economic systems are moot. We’re rearranging the chairs on the Titanic and telling ourselves everything will now be fine.

As I suggested previously “The ability of us naked, story-telling apes to employ a variety of tools (from agriculture to modes of economic production, and everything in between — but especially leveraging energy from hydrocarbons) to influence our resource extraction and use — has turbo-charged our natural growth/expansion tendency.”

Basically, what I guess I am arguing is that similar to other ‘tools’, our economic systems and their subsystems have been additive to our instinctual behaviours to grow. They are making a bad situation worse, as are many of our species’ other ‘tools’. Eliminating or reducing one of these variables in our complex systems is not enough to ‘right the ship’. Nonlinear feedback loops and emergent phenomena are everywhere and impossible to predict, let alone control.

And didn’t this guest post on Rob Mielcarski’s un-Denial site pop up in my email this morning. It argues that humans basically act like every other species on our planet in using whatever resources they can as quickly as they can until resources get harder to access and then the system finds a balanced state [which, in the case of overshoot, will be the result of competition over dwindling resources and very likely a massive die-off]. And while humans are unique in some aspects, we are similar to other species in the most fundamental attributes. We’ve simply been more successful than others because of our opposable thumbs and ‘cleverness’, making us an apex predator within any ecosystem we inhabit.

A ‘Solution’ to Our Predicaments: More Mass-Produced, Industrial Technologies.

Got into one of those social media discussions with someone yesterday morning. The post I was commenting upon is, unfortunately, no longer available and I failed to take a screenshot of it when I originally commented. However, it was from the Globe Content Studio, a content marketing group of the Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail. It was advertising content on the importance of new technologies to address climate change and global carbon emissions.

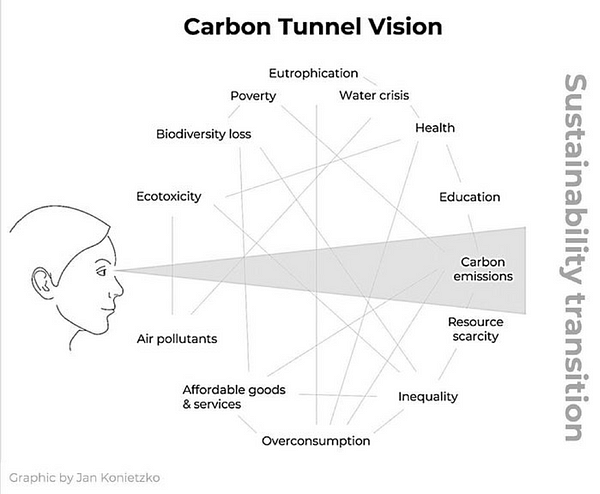

These two images, I believe, are relevant to the conversation that evolved after my original comment:

I have to admit that I’m not sure what this other person thought I was advocating besides wanting to curtail our pursuit of industrial technologies to address atmospheric overloading (and other symptom predicaments of ecological overshoot) but perhaps some readers can discern something I am unable to see.

Keep in mind that I share this dialogue as I have previously to provide a glimpse into the variety of opinions, perceptions, and stories that are being circulated over social media and elsewhere regarding our predicaments and how they might, or might not, be addressed.

Without further ado, here is the conversation and please note that I have copied verbatim and not corrected typos/grammar/etc.).

Me: Complex, industrial technology is what has helped to create our ecological overshoot predicament. More of it only exacerbates the dilemma. Stop marketing the illusion that it can ‘solve’ anything.

WS: Steve Bull the world is not out to “solve”. That is why the Global Energy Transition is called…a transition. What part of that is so difficult yet to grasp. Are you interested in the problem or just dismissing it?

Me: WS, Perhaps you don’t understand the difference between a predicament and a problem. Ecological overshoot is an example of the former — there is no ‘solution’ apart from a correction via Mother Nature.

WS: Steve Bull unless we slow the rate of acceleration by reducing and restricting burning. Exactly what the world has agreed to do. The run away acceleration of warming of the planet and the oceans is a PROBLEM no matter how articulate you try to spin it. So spare me your Bull.

Me: WS, Please peer behind the greenwashed curtains of said energy ‘transition’ being pushed by the mainstream media and politicians. Look at the work of Dr Bill Rees, Dr Simon Michaux, Derrick Jensen, Alice Friedemann, Dr Nate Hagens, Max Wilbert, Erik Michaels, and many others. Attempts to scale up non-renewable, renewable energy-harvesting technologies and their associated products will exacerbate the symptoms of overshoot including atmospheric sink overloading through hydrocarbon use (all of such technologies rely heavily upon them, and they have simply been additive to human energy use over the decades — they have not reduced hydrocarbon use in the least). To say little about the continued destruction of ecological systems through their production, maintenance, and end-of-life reclamation/disposal. There is nothing green, clean, or sustainable about them.

WS: Steve Bull Good grief. More deflective nonsense. So what do you suggest is to be done. Think I will stick with the 250+ scientists from 60+ countries and their collective 3 year study that aligns with NASA and the WHO and MIT reports on the troposphere where 75% of ghg gases reside elevating the ceiling and trapping earth radiated and human induced heat in the lowest level of the atmosphere causing escalation in record heat events…record fires and fire seasons that are full month longer than 100 years ago. Record advancing drought and record hurricanes in frequency and intensity to the extent of “rapid intensification” one day intensity increases. Record hottest years ever recorded and record warming of the oceans. Plain English talk about about the escalation of extreme weather records which 2010–2019 saw the most records broken of any decade in recorded history which was also the hottest decade ever re order and likely both the records and the heat will be broken this decade and the next. Over 580 months without a single below average month for the planet for global mega surface temperatures. All is easily verifiable. I will check the work of the names you mentioned if their names are not on my list of debunked contrarians. Your opinion is very well articulated but still reads as just opinion. You value it..I don’t. I prefer facts.

Me: WS, I don’t disagree with the predicament created by hydrocarbon burning and subsequent atmospheric sink overloading. But I return to my general thesis: it is our technology (that has been supercharged by the leveraging of hydrocarbons) that has led us to our overshoot predicament. Yes, reduce hydrocarbon use but this necessarily includes almost all modern, mass industrial processes including all those required to produce non-renewable, renewable energy-harvesting technologies and their associated products. More technology (that requires industrial processes) is no ‘solution’.

WS: Steve Bull As it is not solvable stating something is not a solution is redundant al…”I don’t disagree but” is just more selection no matter how articulate. Reduction and restriction of emissions across all modes of transportation and burning for energy is the only practical direction which is the agree upon global direction. The rest of you commentary is just dismissive deflection and I believe you know that. You can baffle people with BS but it is little more than a veiled vested interest in the status quo. Necessity fuels innovation and the debate is really over so I will take your point but don’t really see the point of it other than dismissive deflection.

Me: WS, We will have to agree to disagree then. The laws of thermodynamics (especially pertaining to entropy) and the biological principles of ecological overshoot trump what us naked, story-telling apes wish or hope for, especially as it pertains to supposed human ingenuity and our technological prowess. Here’s a recent paper by Dr Bill Rees that might help inform you on these issues: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353488669_Through_the_Eye_of_a_Needle_An_Eco-Heterodox_Perspective_on_the_Renewable_Energy_Transition

WS: Steve Bull I do t need to be informed so don’t be condescending . Theory is irrelevant in terms of the facts the drive the global direction that is necessary to attempt to slow down the rate of accelerating warming or planet and oceans leading to exponential decadal increase in disaster costs and economic loss and the potential tipping point collapses of multiple feedback loops. You ever been in a disaster Steve? Theory is rather irrelevant

Me: WS, So, you’re interested in just the facts but refuse to read more widely the researchers who have a different story to tell than those who support your perspective? You accuse me of supporting more of a status quo path when I am suggesting a significant reduction in technology but you are arguing for replacing that technology with other industrial technology — which is much more a status quo path. And all the while you are saying that I am deflecting…sounds more like you’re projecting your behaviour onto me. Again, we must agree to disagree on this. Enjoy the remainder of your day, I have better things to do than continue to engage in what is increasingly a pointless debate.

WS: Steve Bull at least I am debating facts and not theory and perspective. We definitely disagree as the debate is really over and actions have been agreed upon. I don’t have a perspective Steve. I have only a decade of research and following of weather records and climate altering extreme weather events. While you ponder your perspective your children if you have them and their children will have to live through devastating life threatening extreme events the likes that have never been seen other than cataclysmic events. You break an ice cube into smaller pieces and the melting pendulum cannot be stopped. So either it continues to get to hot to live in some places with wet bulb temperature potentials …or…the unstoppable melting slows or stops the currents that regulate climate. We simply waited too long debating the warnings and now action is needed to try and slow it down..not stop it or reverse it. Theory and perspective are at this point completely irrelevant. So drop out of this pointless debate in your opinion. I am happy to have the last word.

Me: WS, In reading through our discussion I believe that we may be speaking past one another. I am and believe that I stated that I agree with the predicament of atmospheric sink overloading, which seems to be your position. Correct me if I am wrong. My initial comment was a challenge of the approach being pushed to address this predicament: more mass-produced, industrial technology. It was not to deny nor deflect a concern for emissions. In fact, my point is that to reduce this consequence of human impacts upon our planet as well as the other planetary boundaries we have broached (such as biodiversity loss, land system changes, biogeochemical flows, etc.), we need to be reducing our industrial technologies, significantly — especially because they all require the continued use of hydrocarbons (and exponentially increasing use if we attempt to replace much or most of our current technologies). This perspective is not theoretical in nature as you suggest. It is factual. Modern, industrial processes cannot continue or expand without hydrocarbons, except perhaps on the margins in very limited ways. Want to mitigate atmospheric sink overloading (and the other boundaries)? We cannot do it via massive expansion of technologies as is being marketed (by those who stand to profit from this, not surprisingly), we need to reduce human population, consumption, and complex technologies.

WS: Steve Bull well we seem to have been cut of for some reason as I cannot load the post of see your comments where you suggested I did know the difference between predicament and problem. Predicament is soften terminology to what is a problem and life threatening one at that. You still are theorizing and discussing philosophy of perspective. I think that is deflection even if it is a predicament. It is not practical to stop technology or production at this point in time as action to drastically reduce burning is a practical action for the situation. Truthfully do you how a way to reduce population in any kilns of significant manner and do you know anyone that will voluntarily sacrifice their lifestyle. Humanity is addicted to comfort and convenience and your they is not applicable for a large enough scale. So talking about is not changing what needs to change now to even slow down the rate of extreme weather. Or just for lost lives and homes and entire towns but for the unsustainable quadrupling of extreme weather related disaster costs and economic loss. Politicians have to protect employment levels and that requires feeding the machine. We just have to do so without burning. Period. So you keep theorizing and I will debate facts and current events. I have been doing this for a very long time and have seen the extent of regurgitated deflection sponsored by organized and funded misinformation campaigns with what about isms and cherry picked data and you tube contrarians. While you may be 100% right of what is needed it still is deflection of the action necessary right now. It simply is not practical to stop the prosecution. Only innovate that so it better and and in the meantime we must agree to reduce and restrict emissions whenever and however possible. You are clearly more educated than me but education does not always equate to acquired knowledge. Happy holidays. I don’t know whether I May internet is sketchy or once again I have been sensores which has happens many times as my views that may be considered wrong by many are disliked but many as well. Especially if I bring up what the militaries are doin got prepare for the inevitable while the debate is allowed to be perpetuated. Which is what your entire dialog feels like to me.

To EV Or Not To EV? One Of Many Questions Regarding Our ‘Clean/Green’ Utopian Future, Part 1.

Today’s Contemplation has been prompted by my recent thoughts regarding the debate around the uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), their place in a world experiencing the predicament of ecological overshoot (and its various symptom predicaments but especially atmospheric sink overloading), and the competing narratives as to whether EVs can address in any way the environmental/ecological concerns and/or resource constraints/depletion that is at the forefront of discussions.

I’ve seen a recent array of arguments by proponents of EVs highlighting the increase in sales over the past few years[1], with some even using these relatively short-term trends to suggest that the end of the internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles is nigh[2] — and, for a few, that the world is ‘saved’[3]. I have my doubts and the following are some of the reasons why.

While the eventual ‘end’ of ICE vehicles is increasingly probable, it will likely be due to the ever-increasing impact of waning liquid, hydrocarbon fuel supplies and associated cost increases, not the burgeoning transition to EVs its cheerleaders are crowing about. Even government mandates[4] will unlikely create the widespread adoption of EVs advocates are demanding/encouraging as these directives will likely be cancelled or pushed further and further into the future as increasingly economically-challenged citizens rebel against them and various headwinds arise[5]. What we may experience is a curtailing of personal ICE vehicles for many as fuel supplies dwindle and are overwhelmingly taken up by the privileged sitting atop society’s power and wealth structures who can afford/access them — particularly in nations that control hydrocarbon resources. Of course, only time will tell how this all plays out both spatially and temporally.

The first thing to consider is that uptake on the margins by those with the financial ability to be early adopters of EVs does not a long-term trend make. This is especially so with smallish numbers of new purchases having outsized impacts on percentage increases in the early stages of availability. Early trends can be quite misleading and not truly representative of long-term ones. Bubbles happen in technology adoption and the initial euphoria can quickly peter out[6]. This may be what we are seeing with EVs; again, only time will tell.

It is estimated there were 1.4 billion motor vehicles on the roads in 2019[7] (excluding heavy construction equipment and off-road vehicles). In 2022, approximately three out of every twenty new car sales were EVs[8]. And while these vehicular sales can be marketed as monumental based upon comparisons carried out over a short-term perspective, it would take many years of such growth in sales to replace even half of the more than a billion ICE vehicles on the road[9]. Should this early sales growth slow (as some have argued — see below), then replacing over a billion ICE vehicles will take decades; if it happens at all.

Leaving without much comment at all the resource constraints that exist regarding the energy storage components that would be needed for this stupendous feat[10] — and the strain on existing electrical power production and its infrastructure[11] — there exist a number of impediments to a continuing increase in EV adoption suggesting the claims by their cheerleaders to be hopium-laced predictive tales rather than a reflection of on-the-ground reality; especially for a world experiencing diminishing returns on its investments in complexity and well into ecological overshoot — particularly with regard to finite resource depletion and associated shortages.

Perhaps one of the largest deterrents to the mass adoption of EVs is the cost[12]. Cost is a huge factor for many (most?) individuals/families when considering the purchase of a vehicle. This is as true for the purchase of an ICE vehicle as it is for an EV but there exists a variety of cheaper, used vehicles that allow more affordable price points in the ICE realm. Even given these less expensive options, the reality is that purchasers are struggling to afford personal transportation vehicles.

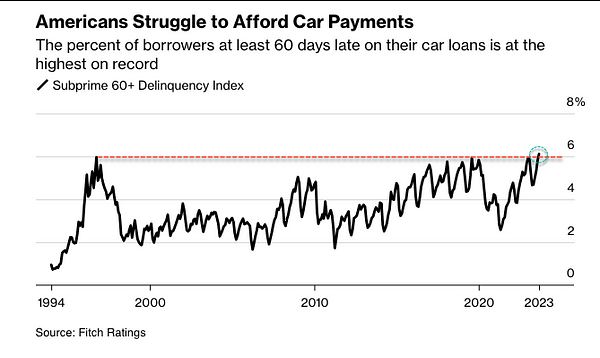

As a recent Zerohedge article highlighted for American car purchasers, an Edmunds analyst told Bloomberg News that: “We’re in this situation where combined with the cost of the vehicles being so high and the interest rates being so historically high, you have a lot of people who are in bad car loans.” As a result, “…the percentage of subprime auto borrowers at least 60 days past due in September topped 6.11%, the highest percentage ever.”

This may change with time but it’s not the current reality, and for potential EV purchasers there are growing concerns over battery degradation leading to declining range ability and more rapid cost depreciation for used EVs to consider[13]. Not only can EVs be substantially more expensive at the outset[14], reports of much higher repair costs[15] are beginning to surface and inhibiting purchases. Again, this may change over time if their uptake continues to grow but it’s a significant concern for cash-strapped families/individuals.

More and more families/individuals are struggling with price inflation of basic goods and services, let alone having to replace high-cost items such as increasingly ‘encouraged/mandated’ ‘low-carbon’ home heating appliances and transportation vehicles. In addition, government economic support via various incentives for EVs is beginning to be withdrawn[16].

‘RealClear’ publications have a fairly obvious bias/bend to them, but this particular article highlights a not so ‘hidden’ aspect of the ‘electrify everything’ narrative: the substantial government subsidies/incentives that has been driving the growth in non-renewable, renewable energy-based technologies (NRREBTs). These financial supports are quite widely publicised by our virtue-signalling politicians looking for brownie points with the public giving credence to the argument that without such incentives by governments (using taxpayer funds and hidden price-inflation taxes) the growth in these products would not be anywhere close to what they have been in recent years.

Countering this point has been the assertion that the main reason NRREBTs have not been widely purchased and sought after is due to oil and gas-industry subsidies[17] (and their massive negative propaganda), a practice that must stop — except for NRREBTS, and these should be increased in one form or another[18].

Digging further into recent data and policy changes (and despite counter-narratives bestowing the incredible recent increase) it would appear that growth in the pickup of EVs is/or is expected to stall/fall as these incentives/subsidies are removed[19]. Once again, only time will tell since it’s difficult to make predictions — especially if they’re about the future.

One other aspect of supposed EV sales records is the emerging evidence of channel stuffing[20] that is occurring. This is a deceptive sales practice that sends products to retailers in quantities far beyond their ability to sell them, but count the inventory as ‘sales’ thus influencing statistics. This has occurred for some time with regard to ICE vehicles[21] and is now being seen with EVs[22].

On top of the considerations described above, there are others who are extremely skeptical of the much ballyhooed benefits of such technologies from an environmental perspective. The production of both EVs and ICE vehicles have tremendous negative impacts upon our ecological systems. Perhaps the most salient differences being discussed are the fuel sources and the impacts of these. It’s not as simple, however, as one being much less destructive than the other and therefore the obvious choice to pursue and mass produce.

I will explore this further in Part 2…

[1] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[2] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[3] See this, this, and/or this.

[4] See this, this, and/or this.

[5] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[6] See this, this, and/or this.

[8] See this.

[9] See this, this, and/or this.

[10] See this, this, and/or this.

[11] See this, this, and/or this.

[12] See this, this, and/or this.

[13] See this, this, and/or this.

[14] See this, this, and/or this.

[15] See this, this, and/or this.

[16] See this, this, this, this, and/or this.

[17] See this, this, this, and/or this.

[18] See this.

[19] See this, this, this, this, this, and/or this.

[20] See this.

January 25, 2022

The ‘Predicament’ of Ecological Overshoot

The following contemplation has been prompted by some commentary regarding a recent article by Megan Seibert of the Real Green New Deal Project. It pulls together a couple of threads that I’ve been discussing the past few months…

There is no ‘remedy’ for our predicament of ecological overshoot, at least not one that most of us would like to implement. While it would be nice to have a ‘solution’, we’ve painted ourselves into a corner from which there appears to be no ‘escape’ — for a variety of reasons.

Most people don’t want to contemplate such an inevitability but the writing seems to be pretty clearly on the wall: we have ‘blossomed’ as a species in both numbers and living standards almost exclusively because of the exploitation of a one-time, finite cache of an energy-rich resource that has encountered significant diminishing returns but whose extraction and secondary impacts have led to pronounced and irreversible (at least in human lifespan terms) environmental/ecological destruction; this expansion of homo sapiens has blown well past the natural carrying capacity of our planetary environment and like any other species that experiences this the future can only be one of a massive ‘collapse’ — both in population numbers and sociocultural complexities.

Also like every other animal on this planet, we are hard-wired to avoid pain and seek out pleasure. But unlike other species we have a unique tool-making ability that we can use to help us address this genetic predisposition. So instead of accepting our painful plight and because of our complex cognitive abilities we have crafted a variety of pleasurable narratives to help us deny the impending reality — few of us ‘enjoy’ contemplating our mortality, so we avoid it or create comforting stories to soothe our anxieties and reduce our cognitive dissonance (an afterlife of some kind being one of the most common).

Throw on top of this the propensity for those at the top of our complex social structures to leverage crises to meet their primary motivation (control/expansion of the wealth-generation/extraction systems that provide their revenue streams and positions of ‘power’), and we have the perfect storm of circumstances to craft soothing stories of ‘solutions’ — especially through industrial production of ‘green/clean’ energy.

Conveniently left out of these tales (through both omission and commission) are the ‘costs’ of these ‘remedies’:

1) The actual unsustainability of industrial products dependent upon finite resources, including the fossil fuel platform.

2) The environmentally-/ecologically-destructive extraction and production processes required to construct, maintain, and then dispose of these ‘clean’ products.

3) The impossibility of any proposed energy alternative to fossil fuels to support our current energy-intensive complexities.

4) The social injustices being foisted upon peoples in the regions being exploited for many of the resources required for ‘green’ products.

5) The geopolitical chess games being played primarily over control of the resources — and the very real possibility of large-scale wars because of these.

6) The highlighting of immediately perceived benefits but the hiding of externalised negative consequences (that is made easier because of temporal lags in some of the effects).

Our propensity for ‘trusting’ authority combines with our desire to deny negative outcomes and leads the vast majority of people to believe that the oxymoronic solution of ‘green’ energy is real and achievable. Not only can we overcome the unfortunate consequences of our growth, but we can transition and sustain, no, improve, our standards of living if only we pursue with all our resources (both physical and monetary) the production of technologies cheered on by our ‘leaders’ — who just happen to profit handsomely from this. All it takes is belief…and, of course, the funnelling of LOTS of fiat currency into the hands of the ruling class.

Adding to the complexity of all of this, we walking/talking apes are highly emotional beings and loss impacts us significantly. We go through a rather complicated grieving process to come to grips with the negative emotions that accompany loss. The increasing recognition that we exist on a finite planet with finite resources and that we have reached or surpassed a tipping point in what we can ‘sustain’ of our social and physical complexities brings significant grief — few want the good times or conveniences to ever end. We experience a variety of stages in coming to accept our loss. Psychologist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross first proposed a five-stage process for this: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance.

Most people, I would argue, are in one of the first three stages at this particular juncture of time. Many are still in complete denial. They continue to believe that things will work out just fine and that the Cassandras shouting about the apocalypse are just plain ‘kooky’. There are some who are indeed quite angry and they are protesting and demanding that our political systems address our issues. They are pushing back hard against the status quo systems, upset that they have been misled on many fronts. Then there are those who are bargaining hard and clinging to the idea that we can ‘tweak’ our current systems or find some ‘solution’, especially through the use of our technological prowess and resourcefulness.

Then there are those few who have moved into the acceptance stage. They recognise what has happened and what will happen. They have acknowledged the inevitability that the complex systems that we rely upon are well beyond our capacity to alter, except perhaps at the margins.

This is not to say those who have reached the acceptance stage have completely ‘given up’, which is an accusation often hurled by those in the earlier stages of grief — and usually along with a LOT of ad hominem attacks. Indeed those who I know accept our predicament are still ‘fighting’, as it were. They are attempting to: alert/inform others so as to not make our situation ever worse (which is exactly what technological ‘solutions’ do); pursuing marginal changes such as increasing the self-reliance/-sufficiency of local regions by advocating relocalisation and regenerative agriculture/permaculture, and/or advocating degrowth; and/or seeking solace through faith of some kind.

No one, not one of us gets out of here alive. Whether some of us or our descendants make it out the other side of the bottleneck we have created for ourselves is up in the air. I wish the stories that have been weaved about ‘renewables’ and the future they could provide were true but I’ve come to the realisation that the more we do to try and prolong our current energy-intensive complexities, the more we reduce the chances for any of us, including most other species (at least those that we haven’t already exterminated), to have much if any of a future.

A couple of relevant articles/links in no particular order of importance:

January 15, 2022

Decline of ‘Rationality’

Got involved in a discussion after an Facebook Friend (Alice Friedemann, whose work can be seen here) posted a study on the decline of ‘rationality’ over the past few decades.

My initial response was as follows:

My initial thought is that this shift is more the result of a paradigmatic shift in academia itself from ‘Modernism’ to ‘Post-Modernism’ that has slowly filtered into the mainstream than anything else. As a university student during the entire decade of the 1980s, I was exposed to A LOT of Post-Modernist philosophy that questioned ‘Rationality’. Off the top of my head I recall a number of the philosophies I was exposed to coming from such academics as: Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Claude Levi-Strauss, Michel Foucault, Clifford Geertz, Friedrich Nietzche, Martin Heidigger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Stephen Jay Gould, G.W.F. Hegel, H.G. Gadamer, Thomas Kuhn, and Jurgen Habermas. The topics included: rationality, literary criticism, deconstruction, deconstructive criticism, hermeneutics, philology, metaphysics, and dialectics. These all reflected a questioning of the strict ‘factual’ or ‘rational’ universe at one level or another — especially the ‘subjectivity’ verses ‘objectivity’ aspects of ‘science’. Here’s just a few of the books I still have in my dwindling collection:

The conversation has brought back some of my interests that arose during my university education (the ten years were in the pursuit of four degrees from biology/physiology to psychology/anthropology that culminated in an M.A. in archaeology and B.Ed. for a career in education; retired almost ten years now). It’s been a while (decades) since I studied this stuff but here are my two cents on the topic:

There is definitely a difference between the hard/physical sciences and the soft/social ones. Measuring and observing chemical reactions, the movement of stars, or biological/physiological properties then projecting their past and/or future states is quite different then doing this when humans are involved in the equation, be it psychology, economics, history, etc..

Perhaps one of the reasons that the Post-Modern era occurred was the result of the social sciences attempting to legitimise their fields as ‘science’ in order to be taken more seriously. Regardless, I still believe humans cannot ever be ‘objective’, especially about themselves; there are just too many psychological mechanisms affecting our cognition. Then there are the ‘incentives’ that exist in research and academia that impact ‘science’; not only the interpretation of results but their use and distribution/publication.

I also believe that as an endeavour practised by very fallible human beings science cannot help but be ‘subjective’ in nature. On more than one occasion we can see the exact same physical evidence being ‘interpreted’ in diametrically-opposed ways by ‘experts’ in the same field, and consensus, if it does occur, can sometimes take place as a result of persuasiveness and influence of a group rather than as a reflection of the evidence itself. This makes one of the more important aspects of science, the modelling of future states, even more problematic — to say little about our ‘interpretations’ of past states.

Throw complexity, non-linearity, and chaos into the mix and everything becomes less prone to accurate modelling and interpretation, no matter how sophisticated or how much data is input. In fact, the more data and more complex the model the more prone it is to error, especially due to the assumptions that tend to get built into them. The smallest of input errors can result in the largest of output result errors.

Certainly there are some models and projections that are better than others and evidence leads to ‘laws’ that are for the most part, irrefutable; but for better or worse, science tends to work on probabilities and rarely absolutes, with the passage of time being the verification of how accurate the base assumptions and model are.

So, I think we need to be careful as Post-Modern thought is challenged and rejected that the pendulum doesn’t swing too far the other way and as some are doing attempt to place science upon a pedestal from which it cannot be questioned or criticised, ever. I’ve run into individuals who will not accept any questioning of ‘science’ or criticism of the endeavour. As soon as you pose a question you are labelled a ‘denier’ and ignored or attacked. Science is absolute, irrefutable, and always correct. Always.

One of the dangers I’ve observed in an unquestioning faith in ‘science’ becomes the increasing leveraging of cherry-picked science by the ruling class to justify/rationalise policy and/or actions; something that has happened in the past and that we seem to be seeing more and more of with it being accompanied by the insistence that the policy/action taken is absolutely correct, cannot be questioned, and anyone critical is anti-science, anti-rational, anti-government and should be silenced, ostracised, marginalised, deplatformed, etc., etc.. And it could very well be that the apparent increasing questioning of ‘science’ is the epiphenomenon of people questioning the ruling class, not necessarily the scientific process itself.

And while the above beliefs of mine may appear as anti-science to some I would argue they are not. They are simply critical awareness of the fact that science is an endeavour practised by very fallible human beings that live in a social world where they are pushed and pulled in numerous directions by a variety of forces that can and do influence the way they think and interpret their physical world. Add to this the (ab)use of ‘science’ by the ruling class and we have the perfect environment for controversy beyond a simple reflection about the human aspects of the practice of science.

We have to be very careful that science does not become a cult where its adherents are ‘righteous’ and ‘better than the others’ because of their ‘correct’ beliefs. That sounds an awful lot like using science to create a new religion to me.

I close with a passage near the beginning of an article on the idea of a ‘renewable’ energy transition by Professor Emeritus Dr. William Rees and Meghan Seibert that I believe is relevant:

“We begin with a reminder that humans are storytellers by nature. We socially construct complex sets of facts, beliefs, and values that guide how we operate in the world. Indeed, humans act out of their socially constructed narratives as if they were real. All political ideologies, religious doctrines, economic paradigms, cultural narratives — even scientific theories — are socially constructed “stories” that may or may not accurately reflect any aspect of reality they purport to represent. Once a particular construct has taken hold, its adherents are likely to treat it more seriously than opposing evidence from an alternate conceptual framework.”

A few ‘related’ articles:

Fiat Currency Devaluation: A Ruling Elite ‘Solution’ to Growth Limits

Today’s post is my comment on the latest Honest Sorcerer’s piece regarding the misuse of the term ‘inflation’ and how currency devaluation and the coming energy squeeze overlap.

Another well-articulated summary of yet a further aspect of our species’ predicament brought about by a society’s attempts to pursue infinite growth on a finite planet and how our ruling class attempts to keep the party going for a tad longer (mostly for them and their ilk) as we bump up against and try to ignore the planet’s biogeophysical limits to growth.

Debauching a currency as a society continues to expand but encounters diminishing returns on its investments in complexity has a long and storied history. In fact, the ‘strategy’ of economic machinations of this type to kick-the-can-down-the-road as it were has been around for about as long as complex societies and their currencies have been. The most famous (at least for those schooled in Western cultures) is that of the multi-generational devaluation of the Roman denarius[1].

I penned a rather lengthy Contemplation on the economic manipulation we will experience increasingly as part of a series on our energy future. In this fourth and final installment (that aligns with your piece) I begin with this:

“In Part 1, I argue that energy underpins everything, including human complex societies. In Part 2, I suggest that the increasing need for diminishing resources, especially finite or limited ‘renewable’ ones, invariably leads to geopolitical tension between competing polities. Part 3 further posits that this geopolitical competition creates internal societal stresses that are met with rising authoritarianism and attempts at sociobehavioural control of domestic populations by the ruling elite.

Economic manipulation — mostly through the financial/monetary systems of a society, that the ruling caste controls — is part and parcel of addressing the societal stresses that arise as things become more complex (as a result of the problem-solving aspects of a society), competition with other polities increases, resources become more dear, and control of the population takes on greater urgency.”

Pre/history has witnessed this story play out countless times in a rather predictable fashion. First, a society addresses its various problems using the least expensive and easiest-to-achieve ‘solutions’. The surpluses that result from this approach allow for a society to continue expanding (hydrocarbons having strapped powerful rockets to this recurrent tendency). Eventually, however, diminishing returns on these ‘solutions’ are encountered. More expensive and harder-to-achieve ‘solutions’ are then pursued.

Surpluses can stave off having to abandon growth for a while but eventually a point is reached where the masses begin to bear the brunt of the economic contraction that accompanies expansion or even just to maintain the status quo — the elite finding ways to insulate themselves for as long as possible. In a society with a complex economic/monetary system, manipulation via currency devaluation is one of the go-to ‘solutions’ since it can disguise responsibility for the inevitable decline in living standards that are experienced from it while benefitting a few at the top of the power and wealth structures that exist in large, complex societies.

On the surface this approach can appear to be effective, and certainly the narrative managers that work on behalf of the ruling class to steer beliefs amongst the masses stress this to be the case. In reality, however, this currency devaluation is like eating one’s seed corn: it always ends badly, for everyone since it is stealing from the future…

I provide some further thoughts on this phenomena in these posts: Collapse Cometh IV; Collapse Cometh XI; Collapse Cometh XXXII; Collapse Cometh CXII.

Avoiding ‘Collapse’ Awareness

The following is my comment on Alan Urban’s most recent post (see here) discussing his thoughts on why more people are not ‘collapse aware’.

The reasons you cite for most not being ‘collapse aware’ are part and parcel of a variety of explanations for this state of affairs. In my contemplations on the situation I’ve come to the conclusion that a lot of this is due to human psychology and the mechanisms that help us to avoid anxiety-provoking thoughts.

First, we highly-cognitive apes deplore uncertainty and the idea of ‘collapse’ is all about an uncertain future and one in which we have little to no control over events. In response, we tend to grab a hold of stories that portray certainty, especially if they paint a more positive future (thanks optimism bias) — regardless of evidence to the contrary (see my posts that discuss this here and here).

In addition, we humans tend to defer to authority, get caught up in groupthink, strive to reduce our cognitive dissonance, and seek to justify our perceptions of the world (see my series of posts on these, beginning here). These aspects of human cognition make us most susceptible to certain forms of narrative management (aka propaganda), particularly stories that portray a comforting and certain future.

Then there’s what seems our complete and utter blindness to the underpinnings of our complex societies — energy — and the limits of our ability to sustain the quantities required to maintain our living standards (see my post series beginning here on this aspect). That we have been drawing down our primary source — hydrocarbons — at ever-increasing rates as we encounter the headwinds due to diminishing returns is increasingly rationalised away as simply a bump in the road since our ingenuity and technological prowess can address any impediments to our wishes/wants — physics be damned.

Add to the above the idea that perhaps the most important cognitive evolutionary shift for our species may have been where we became aware of our own mortality and then developed ways to deny this reality (see Ajit Varki and Danny Brower’s thesis here). Denying reality has become an entrenched means of reducing our anxiety, and it gets used often; and perhaps increasingly as the world goes sideways and provokes greater instances of uncertainty.

Combine the above with the hierarchical aspects of our social species and complex societies, and our story-telling means of communicating, and we have the perfect mix for why we rationalise away evidence for the impending ‘collapse’ of our current living arrangements and all the conveniences and comforts they afford us — especially in the so-called ‘advanced’ economies that have depended upon the lion’s share of what has been to this point in our history a growing supply of surplus energy.

We ignore the hard biogeophysical limits, we rationalise away the ecological systems destruction wrought by our demands, and we weave comforting narratives to avoid anxiety-provoking thoughts. We live in a world of what appears widely-held false beliefs where challenging them gets you ignored and/or ostracised by those clinging to mainstream notions. It’s often better to raise marginally-related topics and concerns to nudge others along a path of ‘sustainability’ and ‘resilience’ as you suggest rather than confront the hard reality of limits and what overshooting them means to our future…

I penned this more than two years ago as members of the world’s ruling caste gathered for COP26. It’s just as relevant today as these so-called ‘leaders’ gather once again in Dubai, United Arab Emirates for COP28…

_____

Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh XXXI–

Beware the Snake Oil Salesmen: Climate Change and Elite Confabs

“If we are not discussing significant degrowth, however (and we’re not because there’s no money to be made from it and the primary motivation of the ruling class, who control the mainstream narratives, is the control/expansion of the wealth-generating systems that provide their revenue streams), then it would seem we are just creating stories to sell more stuff and people tend to accept them readily because they reduce cognitive dissonance — we recognise we live on a finite planet and infinite growth is not possible (except through extreme magical, Cargo Cult-like thinking) but want to also believe that we can continue to live in our energy- and resource-intensive lifestyles uninterrupted and without significant sacrifice”

Also see: Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh XXXII–

Greenwashing, Fiat Currency, Narrative Management: More On Climate Change and Elite Confabs

November 28, 2021

Energy-Averaging Systems and Complexity: A Recipe For Collapse

Supply chain disruptions and the product shortages that result have become a growing concern over the past couple of years and the reasons for these are as varied as the people providing the ‘analysis’. Production delays. Covid-19 pandemic. Pent-up consumer demand. Central bank monetary policy. Government economic stimulus. Consumer hoarding. Supply versus demand basics. Labour woes. Vaccination mandates. Union strikes. The number and variety of competing narratives is almost endless.

I have been once again reminded of the vagaries of our supply chains, the disruptions that can result, and our increasing dependence upon them with the unprecedented torrential rain and flood damage across many parts of British Columbia, Canada; and, of course, similar disruptions have occurred across the planet.

Instead of a recognition that perhaps a rethinking is needed of the complexities of our current systems and the dependencies that result from them, particularly in light of this increasingly problematic supply situation, we have politicians (and many in the media) doubling-down on the very systems that have helped to put us in the various predicaments we are encountering.

Our growing reliance on intensive-energy and other resource systems is not viewed as any type of dependency that places us in the crosshairs of ecological overshoot and unforeseen circumstances, but as a supply and demand conundrum that can be best addressed via our ingenuity and technology. Once again the primacy of a political and/or economic worldview, as opposed to an ecological one, shines through in our interpretation of world events; and of course the subsequent ‘solutions’ proposed.

Our dependence upon complex and thus fragile long-distance supply chains (over which we may have little control whatsoever) is not perceived as a consequence of resource constraints manifesting themselves on a finite planet with a growing population and concomitant resource requirements but as a result of ‘organisational’ weaknesses that can be overcome with the right political and/or economic ‘solutions’. Greater centralisation. More money ‘printing’. Increased taxes. Significant investment in ‘green’ energy. Massive wealth ‘redistribution’. Expansive infrastructure construction. Higher wages. Rationing. Forced vaccinations. The proposed ‘solutions’ are almost endless in nature and scope.

All of these ‘solutions’ have one thing in common: they attempt to ‘tweak’ our current economic/political systems. They fail to recognise that perhaps the weakness or ‘problem’ is with the system itself. A system that has built-in constraints that pre/history, and population biology, would suggest result in eventual failure.

Archaeologist Joseph Tainter discusses the benefits and vulnerabilities of ‘energy averaging systems’ (i.e., trade) that contributed to the collapse of the Chacoan society in his seminal text The Collapse of Complex Societies.

He argued that the energy averaging system employed early on took advantage of the Chacoan Basin’s diversity, distributing environmental vagaries of food production in a mutually-supportive network that increased subsistence security and accommodated population growth. At the beginning, this system was improved by adding more participants and increasing diversity but as time passed duplication of resource bases increased and less productive areas were added causing the buffering effect to decline.

This fits entirely with Tainter’s basic thesis that as problem-solving organisations, complex societies gravitate towards the easiest-to-implement and most beneficial ‘solutions’ to begin with. As time passes, the ‘solutions’ become more costly to society in terms of ‘investments’ (e.g., time, energy, resources, etc.) and the beneficial returns accrued diminish. This is the law of marginal utility, or diminishing returns, in action.

As return on investment dropped for those in the Chacoan Basin that were involved in the agricultural trade system, communities began to withdraw their participation in it. The collapse of the Chacoan society was not due primarily to environmental deterioration (although that did influence behaviour) but because the population choose to disengage when the challenge of another drought raised the costs of participation to a level that was more than the benefits of remaining. In other words, the benefits amassed by participation in the system declined over time and environmental inconsistencies finally pushed regions to remove themselves from a system that no longer provided them security of supplies; participants either moved out of the area or relocalised their economies. The return to a more simplified and local dependence emerged as supply chains could no longer provide security.

Having just completed rereading William Catton Jr.’s Overshoot, I can’t help but take a slightly different perspective than the mainstream ones that are being offered through our various media; what Catton terms an ecological perspective. And one that is influenced by Tainter’s thesis: our supply chain disruptions are increasingly coming under strain from our being in overshoot and encountering diminishing returns on our investments in them (and this is particularly true for one of the most fundamental resources that underpin our global industrial societies: fossil fuels).

What should we do? It’s one of the things I’ve stressed for some years in my local community (not that it seems to be having much impact, if any): we need to use what dwindling resources remain to relocalise as much as possible but particularly food production, procurement of potable water, and supplies of shelter needs for the regional climate so that supply disruptions do not result in a massive ‘collapse’ (an additional priority should also be to ‘decommission’ some of our more ‘dangerous’ creations such as nuclear power plants and biosafety labs).

Pre/history shows that relocalisation is going to happen eventually anyways, and in order to avert a sudden loss of important supplies that would have devastating consequences (especially food, water, and shelter), we should prepare ourselves now while we have the opportunity and resources to do so.

Instead, what I’ve observed is a doubling-down as it were of the processes that have created our predicament: pursuit of perpetual growth on a finite planet, using political/economic mechanisms along with hopes of future technologies to rationalise/justify this approach. While such a path may help to reduce the stress of growing cognitive dissonance, it does nothing to help mitigate the coming ‘storms’ that will increasingly disrupt supply chains.

The inability of our ‘leaders’ to view the world through anything but a political/economic paradigm and its built-in short-term focus has blinded them to the reality that we do not stand above and outside of nature or its biological principles and systems. We are as prone to overshoot and the consequences that come with it as any other species. And because of their blindness (and most people’s uncritical acceptance of their narratives) we are rushing towards a cliff that is directly ahead. In fact, perhaps we’ve already left solid ground but just haven’t realised it yet because, after all, denial is an extremely powerful drug.

November 25, 2021

Overlooking Ecological Overshoot

Today’s thought was prompted by an Andrew Nikiforuk article in The Tyee and my recent rereading of William Catton Jr.’s Overshoot.

I just finished rereading William Catton’s Overshoot. One of the things I’m coming to better appreciate is Catton’s idea that the ‘Age of Exuberance’ (a time created by human expansion in almost all its forms and mostly facilitated by our extraction of fossil fuels) has so infiltrated our thinking that we tend to view the world through almost exclusively human-created institutional lenses, especially economic and political ones. We have come to think of ourselves as completely removed from nature: we sit above and beyond our natural environment with the ability to both control and predict it; primarily due to our ‘ingenuity’ and ‘technological prowess’.

This non-ecological worldview is still very much entrenched in our thinking and comes through quite clearly in mainstream narratives regarding our various predicaments. Usually it goes like this: our ingenuity and technological prowess can ‘solve’ anything thrown our way so we can continue business-as-usual; in fact, we can continue expanding our presence and increase our standard of living to infinity and beyond (apologies to Buzz Lightyear).

What are by now increasingly looking to be insoluble problems appear to have been solved in the past by two different approaches that Catton describes: the takeover method (move into a different area via migration or military expansion) or the drawdown method (depend upon non-renewable and finite resources that have been laid down millennia ago). On a finite planet, there are limits to both of these approaches.

But because of our tendency towards cornucopian thinking, most analyses overlook the idea of resource depletion or overloaded sinks that can help to cleanse our waste products that accompany growth on a finite planet. It’s all about economics, politics, technology, etc..

Our traditional ‘solutions’, however, have probably surpassed any sustainable limits and instead of being able to rely upon our ‘savings’ we have to shift towards relying exclusively upon our ‘income’ which, unfortunately, doesn’t come close to being able to sustain so many of us. To better appreciate the increasing need to do this we also need to shift our interpretive paradigm towards one that puts us back within and an intricate part of ecological systems. Ecological considerations, especially that we’ve overshot our natural carrying capacity, are missing in action from most people’s thinking.

The first thing one must do when found in a hole you want to extricate yourself from is to stop digging. Until and unless we can both individually and as a collective stop pursuing the infinite growth chalice, we travel further and further into the black hole that is ecological overshoot with an eventual rebalancing (i.e., collapse) that we cannot control nor mitigate. Our ingenuity can’t do it. Our technology can’t do it (in fact, there’s a good argument to be made that pursuing technological ‘solutions’ actually exacerbates our overshoot).

It is increasingly likely that a ‘solution’ at this point is completely out of our grasp. We’ve pursued business-as-usual despite repeated warnings because we’ve viewed and interpreted our predicament through the wrong paradigm and put ourselves in a corner. It is likely that one’s energies/efforts may be best focused going forward upon local community resilience and self-sufficiency. Relocalising as much as possible but especially procurement of potable water, appropriate shelter needs (for regional climate), and food should be a priority. Continuing to expand and depend upon diminishing resources that come to us via complex, fragile, and centralised supply chains is a sure recipe for mass disaster.

November 6, 2021

Greenwashing, Fiat Currency, and Narrative Management: More On Climate Change and Elite Confabs

Today’s missive was motivated by a former student’s (and eventual colleague) question regarding a Facebook Post I made regarding COP-26.

Here’s what I posted:

COP-26. Be aware…

These elite confabs are not about climate, except to leverage the fear factor over it to meet the primary concern of the ruling class: control/expansion of the wealth-generating systems that provide their revenue streams. It’s additionally a marketing expo for ‘green’ energy products; a mechanism for helping to steer the mainstream narratives; and a justification for further enrichment of the elite via massive expansion of fake fiat currency.