The Club of Rome is inextricably linked to the legendary report that it commissioned to a group of MIT researchers in 1972, “The Limits to Growth.” Today, nearly 50 years later, we still have to come to terms with the vision brought by the report, a vision that contradicts the core of some of humankind’s most cherished beliefs. The report tells us that we cannot keep growing forever and that we have to stop considering everything we see around us as ours by divine right.

Not surprisingly, the report generated strong feelings and, with them, there came plenty of disinformation and legends. Some cast the Club of Rome in the role of a secret organization with dark and dire purposes, others aimed at the Limits report, claiming that it was “wrong” or, worse, purposefully designed to deceive the public. I wrote an entire book on this subject (The Limits to Growth Revisited) — in short, most of these stories are false but some contain grains of truth and all of them tell us something about how we humans don’t just deny bad news, we tend to demonize the bearers.

So, there is a peculiar legend stating that the leaders of the Club of Rome disavowed their brainchild, The Limits to Growth and, in doing so, they admitted that it had been wrong, or an attempt to mislead the public. It is an old legend but, as all legends, it is surprisingly persistent and you can still see it mentioned in recent times (for instance, here and here) as if it were the obvious truth. It is not: it is a good example of how disinformation works.

…click on the above link to read the rest of the article…

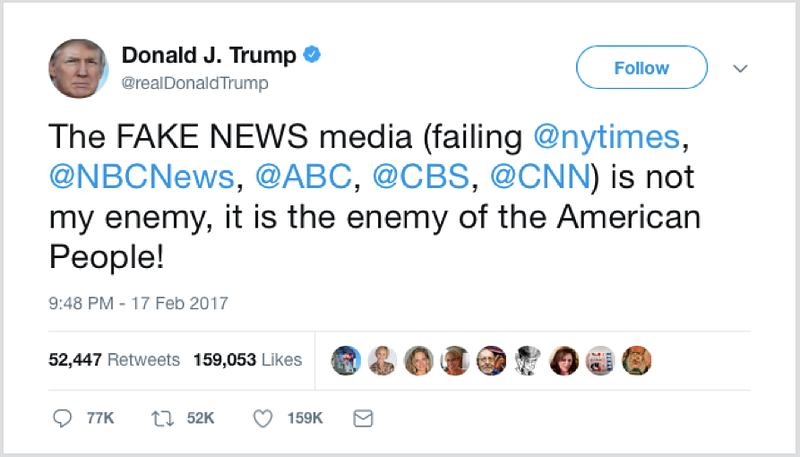

PARIS – How can societies combat the stream of false, often fabricated information that surges across the Internet and through social media, polluting political debates almost everywhere?

That question has bedeviled defenders of democracy at least since the 2016 US presidential election. And at a New Year’s press conference outside the Élysée Palace this month, French President Emmanuel Macron offered his own answer.

Macron’s goal, it seems, is to curtail “fake news” by law. He is promising that, by the end of the year, he will introduce a bill to crack down on those spreading misinformation during any election period.

But France already has a repressive law banning the publication or broadcasting of disinformation in bad faith. Under Article 27 of the famous Press Law of 1881, disseminating false information “by whatever means” is punishable by a fine of up to €45,000 ($55,000) in today’s currency.

The Press Law, however, applies only to information that has “disturbed the public peace,” which can be very difficult to define, let alone prove. Another law, part of the electoral code, provides for punishment of one year in prison and a fine of €15,000 for anyone who uses false information “or other fraudulent maneuvers” to steal votes. But this provision applies primarily to cases of electoral fraud.

Macron’s challenge, then, is to craft legislation for the digital age. Although he didn’t explicitly say so in his recent speech, he is clearly targeting the kind of Russian interference that played a prominent role in the 2016 US presidential election, and also threatened his own presidential campaign last spring.