Currency Devaluation: The Crushing Vice of Price

Devaluation has a negative consequence few mention: the cost of imports skyrockets.

When stagnation grabs exporting nations by the throat, the universal solution offered is devalue your currency to boost exports. As a currency loses purchasing power relative to the currencies of trading partners, exported goods and services become cheaper to those buying the products with competing currencies.

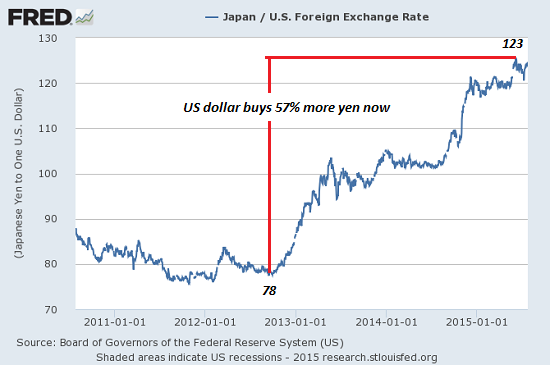

For example, a few years ago, before Japanese authorities moved to devalue the yen, the U.S. dollar bought 78 yen. Now it buys 123 yen–an astonishing 57% increase.

Devaluation is a bonanza for exporters’ bottom lines. Back in late 2012, when a Japanese corporation sold a product in the U.S. for $1, the company received 78 yen when the sale was reported in yen.

Now the same sale of $1 reaps 123 yen. Same product, same price in dollars, but a 57% increase in revenues when stated in yen.

No wonder depreciation is widely viewed as the magic panacea for stagnant revenues and profits. There’s just one tiny little problem with devaluation, which we’ll cover in a moment.

One exporter’s depreciation becomes an immediate problem for other exporters: when Japan devalued its currency, the yen, its products became cheaper to those buying Japanese goods with U.S. dollars, Chinese yuan, euros, etc.

That negatively impacts other exporters selling into the same markets–for example, South Korea.

To remain competitive, South Korea would have to devalue its currency, the won. This is known as competitive devaluation, a.k.a. currency war. As a result of currency wars, the advantages of devaluation are often temporary.

But as correspondent Mark G. recently observed, devaluation has a negative consequence few mention: the cost of imports skyrockets. When imports are essential, such as energy and food, the benefits of devaluation (boosting exports) may well be considerably less than the pain caused by rising import costs.

…click on the above link to read the rest of the article…