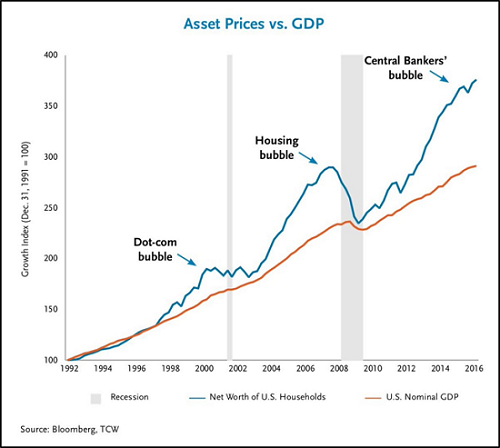

In the next downturn (which may have started last week, yee-haw), the world’s central banks will face a bit of poetic justice: To keep their previous policy mistakes from blowing up the world in 2008, they cut interest rates to historically – some would say unnaturally — low levels, which doesn’t leave the usual amount of room for further cuts.

Now they’re faced with an even bigger threat but are armed with even fewer effective weapons. What will they do? The responsible choice would be to simply let the overgrown forest of bad paper burn, setting the stage for real (that is, sustainable) growth going forward. But that’s unthinkable for today’s monetary authorities because they’ll be blamed for the short-term pain while getting zero credit for the long-term gain.

So instead they’ll go negative, cutting interest rates from near-zero to less than zero — maybe a lot less. And their justifications will resemble the following, published by The Economist magazine last week.

Why sub-zero interest rates are neither unfair nor unnatural

When borrowers are scarce, it helps if money (like potatoes) rots.DENMARK’S Maritime Museum in Elsinore includes one particularly unappetising exhibit: the world’s oldest ship’s biscuit, from a voyage in 1852. Known as hardtack, such biscuits were prized for their long shelf lives, making them a vital source of sustenance for sailors far from shore. They were also appreciated by a great economist, Irving Fisher, as a useful economic metaphor.

Imagine, Fisher wrote in “The Theory of Interest” in 1930, a group of sailors shipwrecked on a barren island with only their stores of hardtack to sustain them. On what terms would sailors borrow and lend biscuits among themselves? In this forlorn economy, what rate of interest would prevail?

…click on the above link to read the rest of the article…