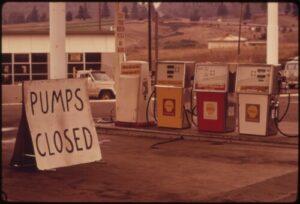

It’s been just over a month since I started talking about how the predictions set out in 1972 by The Limits to Growth were coming true in our time. Since then the situation has become steadily worse. As I write this, rolling blackouts are leaving millions of people in China to huddle in the dark and shutting down yet another round of factories on which the West’s consumer economies depend, while China’s real estate market lurches and shudders with bond defaults. In Europe, natural gas supplies have run short, sending prices to record levels, while in Britain, the fuel they call petrol and we call gasoline is running short as well. Here in the United States, visit a store—any store, anywhere in the country—and odds are you’ll find plenty of bare shelves.

Insofar as the corporate media is discussing these shortages at all, they’re blaming it on the shutdowns last year and on a lack of truck drivers to haul goods to market. They’re not wholly mistaken. During last year’s virus panic, many firms closed their doors or laid off employees, and production of energy resources, raw materials, and finished goods fell accordingly. Now that most countries have opened up again, the energy resources, raw materials, and finished goods needed for ordinary economic life aren’t available, because the habit of just-in-time ordering that pervades the modern global economy leaves no margin for error.

The shortage of truck drivers is another product of the same set of policies. During the shutdown period, many people—truck drivers among them—got thrown out of work. Because of the same regulations that deprived them of work, they couldn’t look for other jobs, and the assistance programs meant to help people deal with the impact of the shutdowns weren’t noticeably more effective than such programs ever are…

…click on the above link to read the rest of the article…