If you have watched the news at all in the last two weeks, you know that there was a huge underwater volcanic eruption near Tonga in the South Pacific Ocean on January 15, 2022, that spewed ash and gases into the atmosphere. It blew with such force that the sound of the eruption was heard in Alaska thousands of miles away and the atmospheric pressure wave it set off has traveled around the earth as many as ten times according to satellite and ground-based sensors. With such a large signal, you might wonder what impact the eruption could have on our weather and climate for the next year. In this post, we will explore how volcanoes in general can affect the climate around the world and whether the Tonga eruption is likely to change our gardens’ climate this year.

What do volcanic eruptions emit into the atmosphere?

When volcanoes erupt they put out both ash and gases. The ash is made of tiny particles of rocky material from solidified lava and sometimes pieces of the volcano destroyed by the eruption. These particles are carried downwind in a direction determined by the winds at the heights to which the ash can rise. In a long eruption, the plume of ash can blow in a different direction each day, covering the ground when it falls back to earth. Usually ash does not rise very high in the atmosphere because it is quite heavy and so most of it falls out in just a few days.

…click on the above link to read the rest of the article…

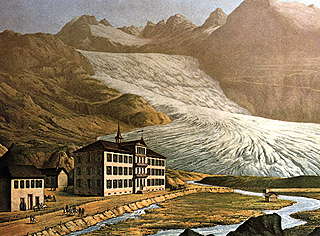

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a recent and significant climate perturbation that may still be affecting the Earth’s climate, but nobody knows what caused it. In this post I look into the question of why it ended when it did, concentrating on the European Alps, without greatly advancing the state of knowledge. I find that the LIA didn’t end because of increasing temperatures, decreasing precipitation or fewer volcanic eruptions. One possible contributor is a trend reversal in the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation; another is an increase in solar radiation, but in neither case is the evidence compelling. There is evidence to suggest that the ongoing phase of glacier retreat and sea level rise is largely a result of a “natural recovery” from the LIA, but no causative mechanism for this has been identified either.

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a recent and significant climate perturbation that may still be affecting the Earth’s climate, but nobody knows what caused it. In this post I look into the question of why it ended when it did, concentrating on the European Alps, without greatly advancing the state of knowledge. I find that the LIA didn’t end because of increasing temperatures, decreasing precipitation or fewer volcanic eruptions. One possible contributor is a trend reversal in the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation; another is an increase in solar radiation, but in neither case is the evidence compelling. There is evidence to suggest that the ongoing phase of glacier retreat and sea level rise is largely a result of a “natural recovery” from the LIA, but no causative mechanism for this has been identified either.